In a 30-square-mile patch of northern Virginia that’s been dubbed “data center alley,” the boom in artificial intelligence is turbocharging electricity use. Struggling to keep up, the power company that serves the area temporarily paused new data center connections at one point in 2022. Virginia’s environmental regulators considered a plan to allow data centers to run diesel generators during power shortages, but backed off after it drew strong community opposition.

In the Kansas City area, a data center along with a factory for electric-vehicle batteries that are under construction will need so much energy the local provider put off plans to close a coal-fired power plant. This is how it is in much of the US, where electric utilities and regulators have been caught off guard by the biggest jump in demand in a generation.

One of the things they didn’t properly plan for is AI, an immensely power-hungry technology that uses specialized microchips to process mountains of data. Electricity consumption at US data centers alone is poised to triple from 2022 levels, to as much as 390 terawatt hours by the end of the decade, according to Boston Consulting Group. That’s equal to about 7.5% of the nation’s projected electricity demand. “We do need way more energy in the world than we thought we needed before,” Sam Altman, chief executive officer of OpenAI, whose ChatGPT tool has become a global phenomenon, said at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland last week. “We still don’t appreciate the energy needs of this technology.”

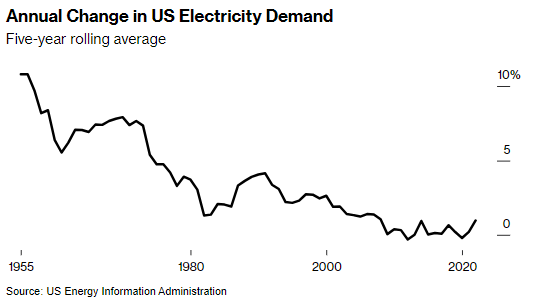

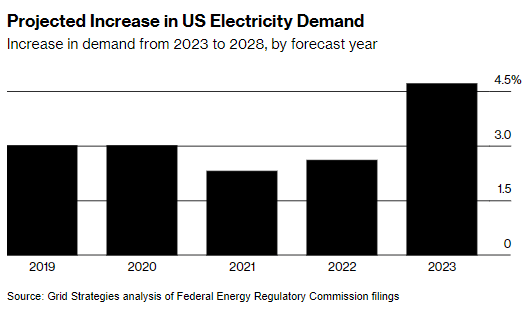

For decades, US electricity demand rose by less than 1% annually. But utilities and grid operators have doubled their annual forecasts for the next five years to about 1.5%, according to Grid Strategies, a consulting firm that based its analysis on regulatory filings. That’s the highest since the 1990s, before the US stepped up efforts to make homes and businesses more energy efficient.

It’s not just the explosion in data centers that has power companies scrambling to revise their projections. The Biden administration’s drive to seed the country with new factories that make electric cars, batteries and semiconductors is straining the nation’s already stressed electricity grid. What’s often referred to as the biggest machine in the world is in reality a patchwork of regional networks with not enough transmission lines in places, complicating the job of bringing in new power from wind and solar farms.

To cope with the surge, some power companies are reconsidering plans to mothball plants that burn fossil fuels, while a few have petitioned regulators for permission to build new gas-powered ones. That means President Joe Biden’s push to bolster environmentally friendly industries could end up contributing to an increase in emissions, at least in the near term.

Unless utilities start to boost generation and make it easier for independent wind and solar farms to connect to their transmission lines, the situation could get dire, says Ari Peskoe, director of the Electricity Law Initiative at Harvard Law School. “New loads are delayed, factories can’t come online, our economic growth potential is diminished,” he says. “The worst-case scenario is utilities don’t adapt and keep old fossil-fuel capacity online and they don’t evolve past that.”

Rob Gramlich, founder of Grid Strategies, says that based on his firm’s projections for peak usage during the summer months, the US could soon be facing a future of rolling blackouts if infrastructure improvements keep getting delayed. “That’s the ultimate concern everybody has: that we’ll be short on power,” he says. At least $20 billion annually needs to be invested in new long-distance transmission lines, but virtually nothing is being spent on them now, he adds.

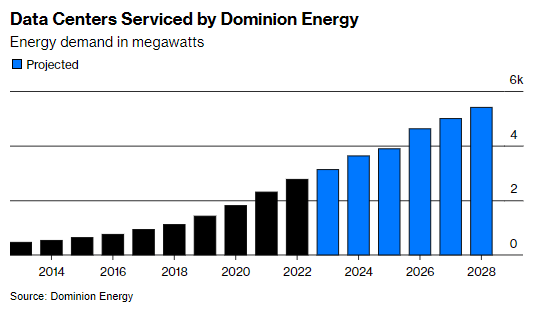

In Virginia, which bills itself as the world’s biggest hub for data centers, about 80 facilities have opened in Loudoun County since 2019 as the pandemic accelerated the shift online for shopping, office work, doctor visits and more. Electricity demand was so great that Dominion Energy Inc. was forced to halt connections to new data centers for about three months in 2022. That same year, the head of data center company Digital Realty said on an earnings call that Dominion had warned its big customers about a “pinch point” that could prevent it from supplying new projects until 2026.

A Dominion representative says this is inaccurate. The pause on new data center connections lasted just a few months, affected only a small area of Loudoun County and had no impact on customers outside of “data center alley,” spokesperson Aaron Ruby said in an email. “After accelerating several new transmission projects, we were able to fully resume service connections and have since connected 27 new data centers in eastern Loudoun.”

Dominion says it expects demand in its service territory to grow by nearly 5% annually over the next 15 years, which would almost double the total amount of electricity it generates and sells. To prepare, the company is building the biggest offshore wind farm in the US some 25 miles off Virginia Beach and is adding solar energy and battery storage. It has also proposed investing in new gas generation and is weighing whether to delay retiring some natural gas plants and one large coal plant.

Utilities are having to contend with other power hogs, besides data centers. There’s about $465 billion worth of semiconductor, EV and battery factories announced since Biden took office, according to White House data, many of them spurred by laws Congress passed in 2022 that give incentives to invest in clean tech and chip fabs.

In Kansas City, construction is underway on a data center run by Meta Platforms Inc., while on the city’s outskirts, Panasonic Holdings Corp. is building a factory where energy-intensive robots will help assemble EV batteries. Both projects, as well as overall economic development in the region, are fueling some of the “most robust electricity demand growth in decades,” said David Campbell, chief executive officer of Evergy, the utility that serves the area, in a June 15 press release. In the same communication, the company said it would delay retiring a coal plant that’s been operational since the 1960s by five years, to 2028.

Soaring electricity demand is slowing the closure of coal plants elsewhere. Almost two dozen facilities from Kentucky to North Dakota that were set to retire between 2022 and 2028 have been delayed, according to America’s Power, a coal-power trade group.

Many tech companies and clean tech manufacturers prefer their plants to be powered exclusively by renewable energy. But those aspirations are running up against reality, says Mark Nelson, managing director of energy consultancy Radiant Energy Group: “Factories say, ‘We want clean energy. At this point we’ll take anything.’”

Some corporations are now being forced to consider locations they had initially overlooked to secure energy within the timeframe they need, such as rural areas in Mississippi, says Didi Caldwell, who’s spent more than two decades helping companies find sites for their facilities and runs a consulting firm in South Carolina.

In Arizona, historic demand prompted the state’s largest utility to temporarily stop accepting new business in the fall from very large data centers that need power around the clock, according to people with knowledge of the matter. Arizona Public Service needed to do in-depth studies on things such as how many transmission lines are needed and where substations will be located before signing contracts, one of the people said.

“The number and the size of requests kept coming,” says Tony Tewelis, who works in APS’s transmission and distribution group, adding that some customers had asked for almost 2 gigawatts of power. “We wanted to make sure that we did our due diligence before we said yes.” APS says it will roll out a new process this year where it will perform case-by-case studies before taking on very large data centers as customers.

Other parts of the world are also seeing big increases in power demand. China’s electricity need is forecast to grow about 6% this year, driven by the manufacturing of things like EVs and solar equipment; in India it’s set to almost double in the decade through to 2032. And London’s aging electricity grid is struggling to add more data centers.

A big power company with operations in six states, Duke Energy has seen unprecedented demand growth, spurred by data centers, factories and EVs—including both manufacturing and charging. It plans to ask regulators for permission to build more gas-fired and solar power projects by the early 2030s. But Glen Snider, who heads resource planning, warns that even with that additional capacity, the company might have to keep some customers waiting if future demand growth outpaced its ability to add new generation and transmission.

“There’s not an infinite ability for resources to be added to the grid,” he says. “So if growth accelerated even further, we might have to delay the timing at which new large loads are added.”