The march toward a low carbon steel production future is at the top of the political agenda and could become a key barometer for some of the most important general elections in Europe in 2024. Steel is a vital commodity, used in all key industries from car manufacturing to white goods and the construction and aerospace sectors. The sector accounts around 8% of annual global greenhouse gas emissions, which will need to be cut by at least 90% for the sector to play a credible role in achieving climate targets. But to achieve those changes, the industry, one of the six so-called “hard-to-abate” sectors, will need to create new jobs, terminate others, adopt new legislation and issue new financing.

A number of projects to produce low-carbon steel kicked off in Europe in 2023, with companies beginning to consult with the public and unions over plans to shut or change their hot end parts. Talks are expected to continue in 2024 while prices for consumer goods will rise as new legislation is enforced.

Because global steel demand is forecast to rise 30% by 2050 from the 1.88 billion mt produced in 2022, according to worldsteel data, the main lever for the steel industry to decarbonize is expected to come from the adoption of low-carbon production processes. For that reason, the industry needs to carry out radical change since steel is such a crucial raw material for so many industries that use steel to cut their Scope 3 emissions.

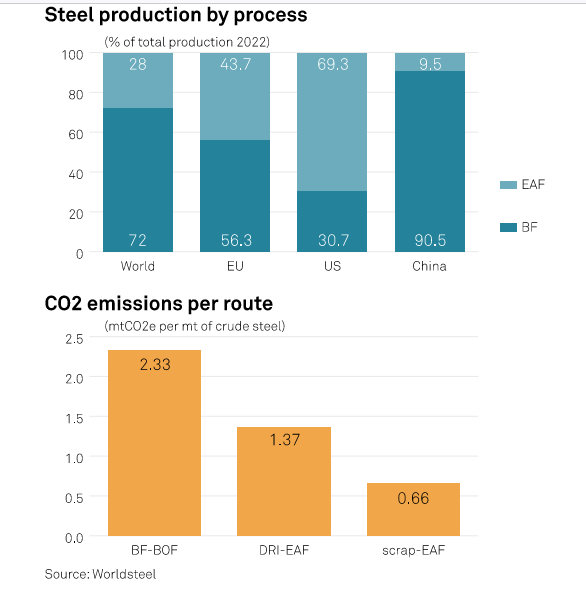

According to worldsteel data from 2022, on average, every metric ton of steel produced leads to 1.91 mt of CO2 emitted. The carbon intensity changes depending on the route and raw materials used to produce steel.

Globally, 72% of steel is made using blast furnaces, the most polluting way to make steel, while 28% is produced using electric arc furnaces.

Hydrogen-based steel making

With EAFs more sustainable, the easy answer is to transform the BFs into EAFs. However, there is insufficient scrap in the world to satisfy global steel demand by making use of this route. The global scrap market is currently estimated at around 600 million-650 million mt and demand is expected to rise to 800 million mt by 2030 and around 1 billion mt by 2050, according to a report published by UK Steel in November, titled “Steel scrap: a strategic raw material for net zero steel”.

For this reason, 43 countries are already taking action to secure their steel scrap supplies, the report said, and the EU is planning to introduce changes to its Waste Shipment Regulation in 2024 to address environmental concerns regarding its scrap exports, putting restrictions on exports of scrap to non-OECD countries.

In Europe, where decarbonization projects are set to cut emissions by 30% in 2030 and entirely by 2050, companies are trying to shift to a middle ground, using hydrogen through a direct reduced process to generate hot metal, which could then be used in an electric arc furnace.

“From our perspective in Europe, we see two main pathways: one pathway is carbon capture and usage and storage, and the other is what we call carbon direct avoidance, which is basically hydrogen-based steel making,” Adolfo Aiello, deputy director general, Climate & Energy at Eurofer, the European steel association, told S&P Global Commodity Insights. “Now during the last few years, we have seen an increase in the number of projects on the second pathway, hydrogen-based steel making, but a lot depends on the surrounding conditions, the local and regional conditions.

“In the short term we have as the main challenges the availability of alternative energy at internationally competitive prices,” he said. “So by alternative energy, I mean natural gas, electricity and hydrogen — that’s the clearest one.”

Unsurprisingly, those companies at the forefront of this are mainly located in northern parts of Europe, where there is more availability of hydrogen.

“In northern Sweden we really rely on the hydropower backbone. So Sweden and Norway, the northern parts of those countries, it’s really now a natural resource comparable to oil. It’s just a massive battery that exists in those locations,” said Joel Ridderstrom, CFO of H2Green Steel. The company is expected to be one of the world’s first large-scale green steel plants to use hydrogen produced from renewable electricity — rather than coal — to deliver steel in a process emitting as much as 95% less CO2 than steel produced using traditional blast furnace technology. In 2023 H2 Green Steel raised over Eur1 billion for a gigawatt-scale electrolyzer project in Sweden, in what has been the largest private placement in Europe this year.

State funding

According to Mike Walsh, a director at the Willy Korf Foundation and one of the hosts of the Green Steel Challenge Podcast, the sector is going to decarbonize one way or another within a reasonable timeframe, although unlikely by 2050. Europe is leading the way in that challenge, he said, but it still needs to find a solution for its energy supplies.

“Various European steel plants are converting their mills from blast furnaces to electric arc furnace routes, and that’s the ‘easier’ way at this time, but there’s a lot of things associated with that, such as access to suitable raw materials: electricity and scrap as well as labor reduction,” said Walsh.

Eurofer’s Aiello said: “In general, we see that when a BF is shut down at least one or two [direct-reduced iron plants] and then eventually some EAFs are planned to be built,” and this means [getting] access to energy and more scrap availability.

DRI demand will rise by 50 million mt by 2032 and 160 million mt by 2050, according to the International Iron Metallics Association.

Considering all these issues, Walsh said about 50% of the EU conversion is likely to be funded by the state in some form or another, but “whether that’s the right thing to do is another discussion.”

But while the funds are indeed another key challenge, so is the way the investment is implemented, Aiello also, pointing out that this year the European Commission has already issued $3.2 billion in green subsidies and introduced the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

The CBAM began its first transitional phase in October. The CBAM is the EU’s landmark tool to fight carbon leakage and one of the central pillars of the EU’s ambitious net-zero target, as it will equalize the price of carbon between domestic products and imports, ensuring that the EU’s climate policies are not undermined by production relocating to countries with less ambitious green standards or by the replacement of EU products by more carbon-intensive imports.

At the UN’s UN Climate Change Conference in December, the World Trade Association adopted a series of “Steel Standard Principles”, marking the first step to establish a unified approach in the production of lower-carbon steel, although market observes said the measure lacked a formal definition.

Supply deals

Many companies in different industries across the steel value chain are reducing their Scope 1 and 2 emissions by implementing energy-efficient technologies, electrifying processes, and using zero-carbon alternatives, but in order to reduce their Scope 3 emissions, which are indirect emissions associated with their value chain, they need low-carbon raw materials. So large companies, such as furniture producers IKEA or car producers like Volvo, Mercedes and Porsche, are buying low-carbon “green” steel in increasing volumes and are agreeing supply deals. In general interest in various low-carbon steel projects is rising.

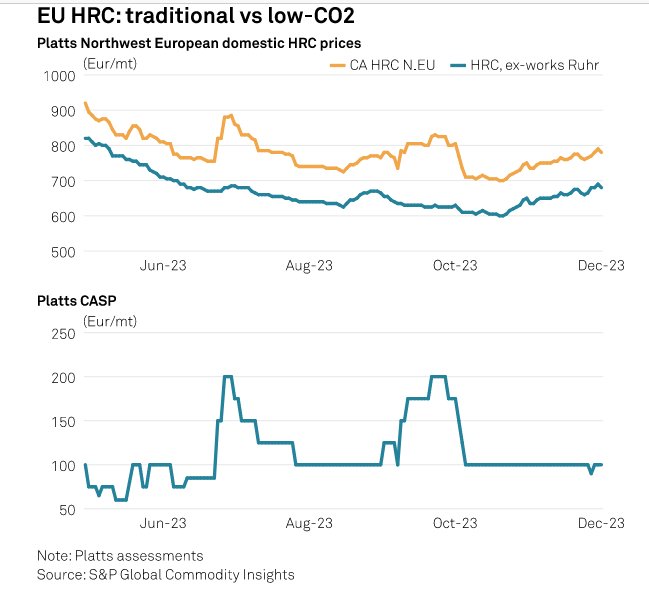

European spot buyers have started to show a greater interest in carbon-accounted steel, but demand for green steel is still significantly lower than for traditional steel. Buyers have started to book either smaller volumes of low-CO2 steel coil in test buying or have been booking back-to-back projects, while a lack of standards defining green steel remains a concern for buyers who do not want to risk putting volumes of any “green” material in stock to later find it does not meet standards. However, most in the industry think that is matter of time when demand for low-CO2 steel will outstrip supply as new projects come into operation after changes to emissions regulations.

Platts, part of S&P Global Commodity Insight, launched its carbon accounted prices in May.