Winter is over. If you’re reading these lines early Monday in Europe, you probably think I’m crazy. Yes, I’m aware it’s frigid in most of the region, with temperatures of -10C in Berlin and -25C in Oslo having finally arrived. But from the perspective of the European natural gas market, you may as well be at the beach.

Let me explain: With nearly half of the heating season in the rearview mirror — the midpoint comes on Jan. 15 — the region’s mild weather until now has left supplies plentiful, making the current cold snap just a blip.

Even if the chill holds for rest of the season, Europe would still consume far less natural gas for heating than in a normal winter. With demand down, regional gas storage isn’t being depleted as fast as expected — or feared. With that comes lower prices. Compared with a year ago, they’re down 45%.

In normal times, the unseasonably mild weather would be unmitigated bad news: another sign of global warming. But right now, the warmth is an economic gift, easing inflation in a continent battling an energy crisis for the third consecutive winter. The loser is Russian President Vladimir Putin, who has used an energy windfall over the last two years to finance his war in Ukraine.

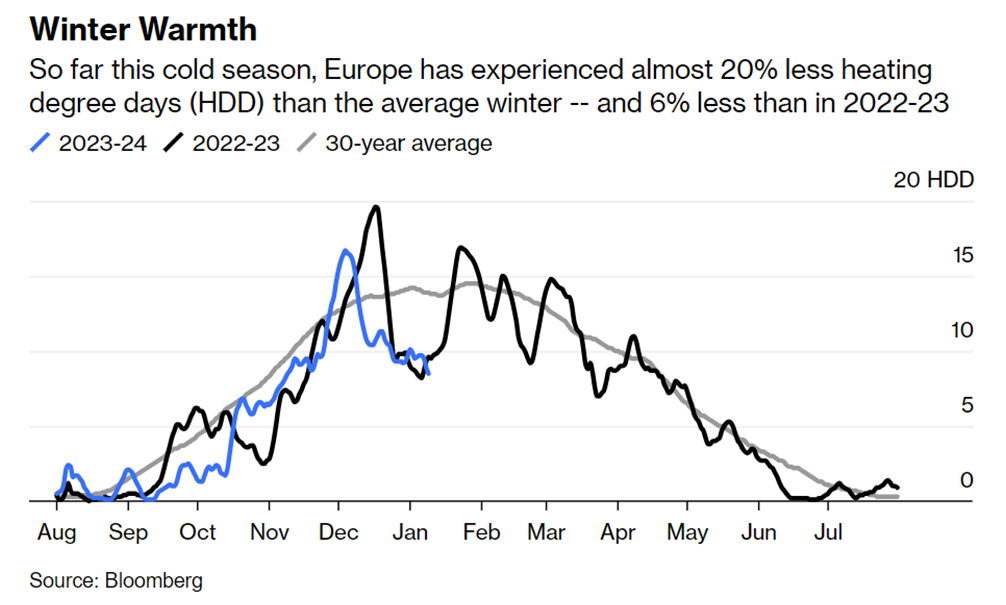

Winter Warmth

Considered in heating-degree days — a measure of how cold a particular location is — northwest Europe has experienced 933 HDDs since the beginning of August. That’s roughly 6% fewer than the 2022-2023 season, another mild winter, and a whopping 19.8% below the 30-year average, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. A high number of heating-degree days results in higher gas use for heating.

The heating-degree days’ tally at the midpoint of the winter is so small that it would take an unusually harsh February and March to bring it back to normal. Even if temperatures go back to the 30-year average for the rest of the European winter, 2023-2024 HDDs would be still almost 10% below the long-term mean, according to my calculations.

The mild weather has induced a massive decrease in gas consumption for heating. That’s on top of greater demand reduction due to energy-intensive companies curbing production. In Germany, for example, output from energy intensive companies, such as chemical plants and metal smelters, is down 20% from before Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

As a result, stockpiles remain well above normal for this time of the winter. Granted, they started the season almost full, compared to the typical 90%. Since then, with consumption lower than normal, they have dropped to about 85%, compared to a 10-year average for early January of about 75%. Under current trends, Europe would reach the spring with more than half its underground gas storage full, versus a 10-year average of just 35%.

Gas Crisis Eases

European natural gas prices have fallen significantly from the record high of the last two winters, but remain well above the 2010-2020 average. Renewable power has also helped, with solar and wind reducing the need for gas. The recovery in French nuclear production last year and the use of coal in Germany have further cut gas consumption too.

The market is pricing that bearish possibility. Benchmark European gas prices last week fell below €35 per megawatt-hour, down from €55 in October. Though prices have fallen sharply over the last year, they remain well above the 2010-2020 average of €20.1 per MWh. As such, they continue to limit economic activity among the most energy-intensive companies.

The combination of mild weather and economic sacrifice has saved the day for Europe. By next winter, more liquefied natural gas should be available, lessening the need for a warm winter. That may not be great news for the planet – but it is for European consumers.