European steelmakers find themselves in an “alarming” situation as they are in the midst of starting investment-heavy technological changes for the energy transition during economic weakness, Tata steel Vice President Henrik Adam said.

Adam, who also serves as Chair of Tata Steel UK and Chair of the Board at Tata Steel Netherlands Holding, discussed in an interview with S&P Global Commodity Insights the challenges of the decarbonization journeys of Tata Steel Europe’s mills in IJmuiden, Netherlands, and Port Talbot, UK. Some GBP750 million ($950 million) is being invested in Port Talbot with Tata Steel yet to unveil investment costs for IJmuiden. The mills have different plans for reducing CO2 emissions from steelmaking and European mills more broadly have been seeking funding to meet CO2 emission levels set by governments.

Tata Steel has been in discussions with various policymakers: The Dutch government, which is still being formed, and the European Commission for the Netherlands and the UK government for Port Talbot.

“You must explain the technological path rationally and economically. It is well-known that investments are needed, and they are enormously large,” Adam said.

“The requirements that politics have set can only be met when subsidies are released for investments while the situation of energy costs need to be clearer amid the current economic situation.”

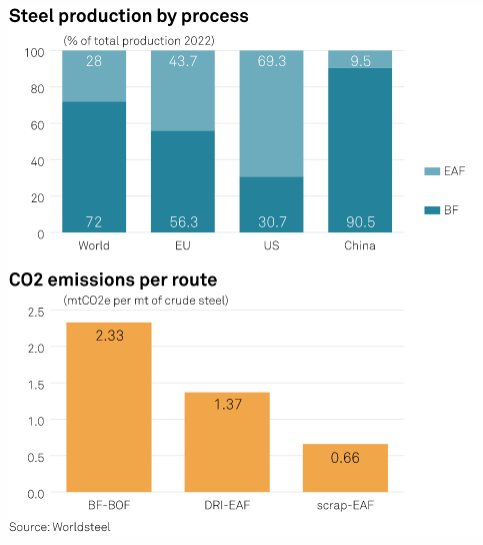

The path to decarbonization has several options as to how to reduce emissions and Tata Steel has done some rethinking with regards to IJmuiden.

“Admittedly, we have changed our concept several times,” said Adam. The first idea was to use carbon capture storage but had then been deemed by higher management as not sufficiently sustainable. “There are uncertainties around CCS and CCU. It can be an option but should not be the basis. There is also the question whether customers would regard this as a green solution.”

Tata decided to go the DRI route and after further deliberations and changing plans, settled for the DRI-EAF route. “These changes of course were not speeding up the process,” Adam said. The Dutch mill is still currently waiting for financial aid by the Dutch government for the decarbonization plans.

“The Dutch government is in an on-going forming process. We are however currently in constructive discussions with government departments and ministries, though I can’t give a prognosis on when a decision will come.”

Tata Steel UK unveiled plans for the Port Talbot mill in January when the UK government said it would inject GBP500 million into the project. The company will replace two blast furnaces with one EAF, cutting capacity 40% to 3 million mt/year.

“We have a decision in the UK now that has been worked on with several governments. It was a long process, but these are not topics that can be discussed within three weeks,” Adam said.

Tata Steel will idle both its blast furnaces by the end of the year and has just shut its coke ovens. While the EAF is being built, the company will import material to process and sell in the UK. The EAF is planned to start production in early 2027, the same time the UK’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will kick in which means there could be an overlap.

When asked on the potential impact on imports by Tata into the UK, Adam said it would be too early to say as the UK has not published detailed information about its CBAM.

“We are aiming to have our own production as quick as possible and are eager to keep the time frame without production short,” Adam said.

UK unions, still campaigning for the continuation of one blast furnace while the EAF is being built, have been voting on a potential strike by Tata Steel workers from mid-April.

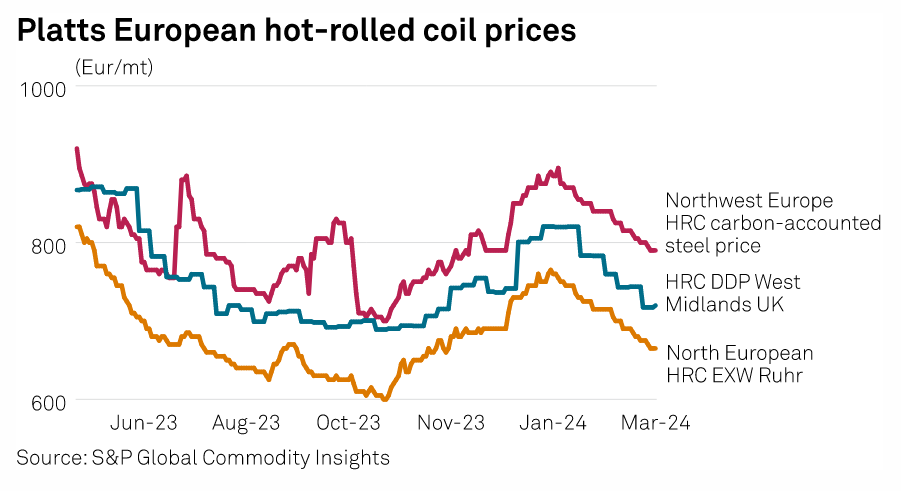

Tata Steel has been saying for years that the Port Talbot mill needed upgrades because it was loss-making. The situation for the wider European steel industry is not easy either, according to Adam.

“The European steel industry was always at the forefront globally, but it is the only region that has shrunk, all others increased or remained stable,” Adam said. “No one can tell me that this is because of a bad structural set-up. It happened because of a combination of cost, export restrictions of other markets and an open market in Europe. Europe had capacity adjustments where it was not economically viable to produce. Other economies decided differently,” Adam said.

EU crude steel production fell 4.4% in 2023 to 126 million mt, while production in Asia rose 0.9% to 1.4 billion mt, according to Worldsteel.

Adam said excess material was still arriving in Europe. “The EU Commission stands for open trade but the current situation for the European steel industry is alarming.”

“The question is if politics wants to act decisively to change the situation. It cannot be expected that the industry comes together as a conglomerate, which is not desired anyway if you look at merger control examples,” he said.

Tata Steel and Thyssenkrupp tried to merge steel assets in 2019, a move blocked by the EC unless divestments were made. The companies abandoned the plan.

“What we will have to do better as an industry is to explain to the public why we need a functioning steel industry and why it needs to be done in certain ways,” Adam said. “We have not been doing it that well … others [industries] have done better.”

“There is no energy transition without steel. No transformers without steel, no electric vehicle without electrical steel, no wind turbines. This needs to be explained.”

Source: Platts