Western governments are increasingly implementing policies to protect their local metal-producing industries from rival products made in the developing world, but how should eastern lawmakers and companies respond to these moves?

Much of the debate surrounding the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the US’ Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has so far centered on how companies hoping to export their products to these jurisdictions might change their production or sourcing processes to abide by the new regulations.

But should governments of developing nations such as India step up and bear the financial burden arising from non-compliance to these rules so their private companies don’t have to?

For Indian recycling industry heavyweight and Gemini Corporation chairman Surendra Borad Patawari, the answer is an unequivocal “yes.”

Speaking at the Materials Recycling Association of India (MRAI) international conference on January 23-25 in Kolkata, Patawari described the new Western regulations as “thinly veiled protectionist and imperialist non-tariff barriers” and said India’s government should “heavily subsidize” the industry to protect it from financial harm stemming from the rules.

On the other hand, Fastmarkets’ principal analyst Miriam Falk said that such a response from the Indian government could lead to trade tensions and retaliation from other nations. She instead argues that a more sustainable approach for the longer-term health of the Indian steel industry would lead the country to focus on enhancing competitiveness and decarbonization.

Protectionist policy sweeps the West

The EU introduced the transitional phase of CBAM from October 1, and it will initially apply to imports of electricity, aluminum, iron and steel, cement, fertilizers and hydrogen into Europe.

Currently, buyers in Europe are obliged to submit declarations on embedded carbon emissions in their imported goods, but do not pay any carbon cost.

From January 1, 2026, imports of these goods into the EU will be charged a carbon levy based on the embedded emissions generated during the production process, which would present a financial burden to the firms involved.

Likewise, the US IRA – signed into law in August 2022 – provides tax incentives to source critical battery raw materials within the US or from free-trade partners. It also includes tax credits intended to promote the sale of electric vehicles (EVs). Two further EU regulations are also expected to have an impact on metal supply chains from developing countries.

Europe’s Critical Raw Materials Act sets clear benchmarks for domestic capacities along the strategic raw material supply chain and to diversify EU supply by 2030. Up to 65% of the EU’s annual consumption of each strategic raw material at any relevant stage of processing can come from a single third country.

And the EU’s overhauled Waste Shipment Regulation (WSR) is expected to make it more difficult to export EU scrap metal considered “waste” to countries that are not members of the Organization for Economic Co-operation & Development (OECD). This is expected to come into force at some point in 2027.

This is therefore a potential concern for consumers of ferrous and non-ferrous scrap in countries such as India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, who may find themselves short on scrap supply.

More subsides needed for India?

While these Western nations see their actions as safeguarding their domestic industry, some leading figures in developing nations such as India believe these actions are hindering global trade.

“This has led to a situation where countries like India meekly queue up with hat in hand, to obey such imperialist [measures like the] CBAM type of non-tariff barriers with which they struggle to comply,” Patawari said at the event, as quoted by the MRAI.

In the case of steel, India is a major exporter of hot-rolled coil to EU nations, and volumes exported to Europe could in the future conceivably be cut if companies in the South Asian nation do not adhere to the carbon emissions rules laid out under CBAM.

“Such thinly veiled protectionist and imperialist non-tariff barriers are meant to erode the advantage of India’s cheaper cost of production,” he said. Instead of complying with the US and EU’s non-tariff barriers, which Patwari said ensure that countries such as India never get to thrive on a level playing field, India too must heavily subsidize Indian industries, he added.

An Indian steel mill source told Fastmarkets that if India were to ramp up its support for its local steel industry, it would be of great help to improve India’s position in the highly competitive global steel markets.

Decarbonization over subsidization?

But increasing state subsidization of India’s steel industry could cause more harm than good, Miriam Falk said.

“While subsidies might offer temporary relief from CBAM and IRA, they could also lead to trade tensions and retaliation from other nations. Instead, a more sustainable approach that focuses on enhancing competitiveness and decarbonization would be prudent for the long-term health of the industry,” Falk said.

Large subsidies have historically been distributed by governments such as China to prop up numerous steel companies, allowing them to export huge volumes of steel to markets such as Europe at low prices.

The practice led to international consternation and prompted the G20 group of nations and members of the OECD to establish a global forum to tackle steel overcapacity.

“Despite some progress, significant challenges persist for India’s steel industry, especially in shifting away from traditional coal-based processes,” Falk said.

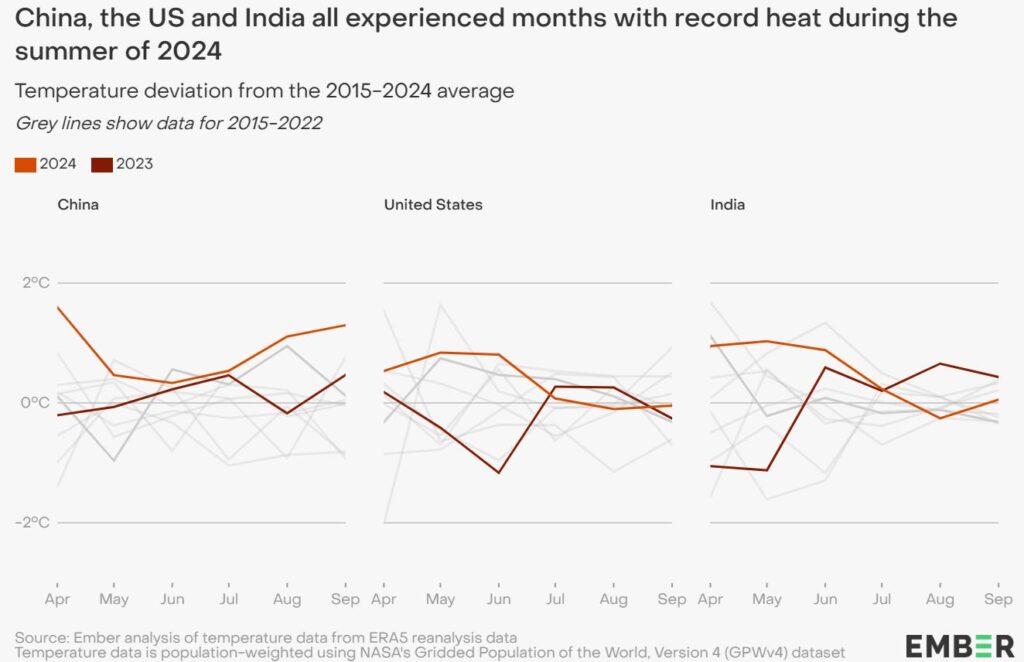

Far from shifting away from blast furnaces (BFs) and basic oxygen furnaces (BOFs), India has become the world’s largest developer of new coal-based BF-BOF capacity, as the above chart shows, according to environmental NGO Global Energy Monitor (GEM).

India holds 40% of such capacity under development in the world, while China is responsible for 39%, according to GEM data.

“To avoid locking in high-emission coal-based steelmaking for decades, it will be essential to retire old blast furnaces,” Falk said. “However, the pace of decarbonization in the steel sector lags, with planned blast furnace capacity in China and India risking prolonged high emissions.”

“The global steel raw materials market is evolving with the adoption of alternative technologies like direct reduced iron (DRI) and hydrogen-based processes, changing demand for iron ore and coal,” Falk said. “Additionally, a focus on recycling and scrap-based production to reduce emissions will increase demand for scrap steel.”

“Beyond subsidies, focusing on competitiveness and decarbonization will be key for continued growth in the Indian steel sector,” Falk added.

India has lofty ambitions for growing its ferrous scrap intake. Minister of steel Jyotiraditya Scindia has stated on many occasions that India’s steel sector should boost its intake to a level where scrap has a 50% share in the country’s steelmaking.

One development running alongside this aim is a rise in orders for new scrap and DRI-reliant electric arc furnaces (EAFs) from major steelmakers such as Tata Steel, which would lead to a rise in not only local buying of scrap but also imports, market sources said.

Indian steel scrap imports jumped by 40% year on year to 11.76 million tonnes in 2023, according to customs data.

Source: Fastmarkets