LAUNCESTON, Australia, Feb 22 (Reuters) – When looking at the commodities used to make steel, iron ore gathers the bulk of headlines given its strong link to the perceived health of China’s economy. But metallurgical coal is also a key input, and this fuel has quietly been a top performer in the energy commodity space in recent months.

Australia dominates the seaborne market for metallurgical coal, accounting for more than half of global volumes, and about three times the shipments of the next biggest exporter, the United States. The price of Australian metallurgical coal, also known as coking coal, on the Singapore Exchange ended at $315 a metric ton on Wednesday. The contracts, which are linked to the free-on-board price in Australia, have risen 40.3% since the 2023 low of $224.50 a ton on July 6.

In contrast, high-grade Australian thermal coal is only 0.5% higher than its 2023 low, while Brent crude oil has risen 13.4% from its low in December, and spot liquefied natural gas is down 2.2% from the weakest it was in 2023. While the price is well below the record $635 a ton reached in March 2022 amid fears to global supplies after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February of that year, it’s still well above the broad $100-$250 range that prevailed from 2018 to mid-2021.

Unlike iron ore, which is dominated by China gobbling up more than 70% of global seaborne volumes, coking coal is a more evenly-spread market with demand centres in both the developed countries of North Asia and the developing nations of South Asia. It’s likely that much of the increase in prices in coking coal in recent years is down to increased demand from India, which has seen imports rise from 53.32 million tons in 2020 to 70.49 million in 2023, according to data compiled by commodity analysts Kpler.

Australia remains the biggest supplier to India, with imports in 2023 coming in at 41.0 million tons, down slightly from 43.22 million the prior year. It’s worth noting that India has turned to Russian coking coal since Moscow’s war on Ukraine, snapping up discounted cargoes that can no longer go to Europe because of sanctions against Russia.

India’s imports of Russian metallurgical coal rose to 11.76 million tons in 2023, almost double the 6.07 million the previous year and four times the 2.63 million from 2021. China’s imports of seaborne coking coal also rose in 2023, reaching 36.8 million tons, up from 27.05 million the previous year. This is largely a reflection of the return of Australian coal to China after Beijing lifted its informal ban, imposed in 2020 amid a series of political disputes with Canberra.

AUSTRALIA RECORD

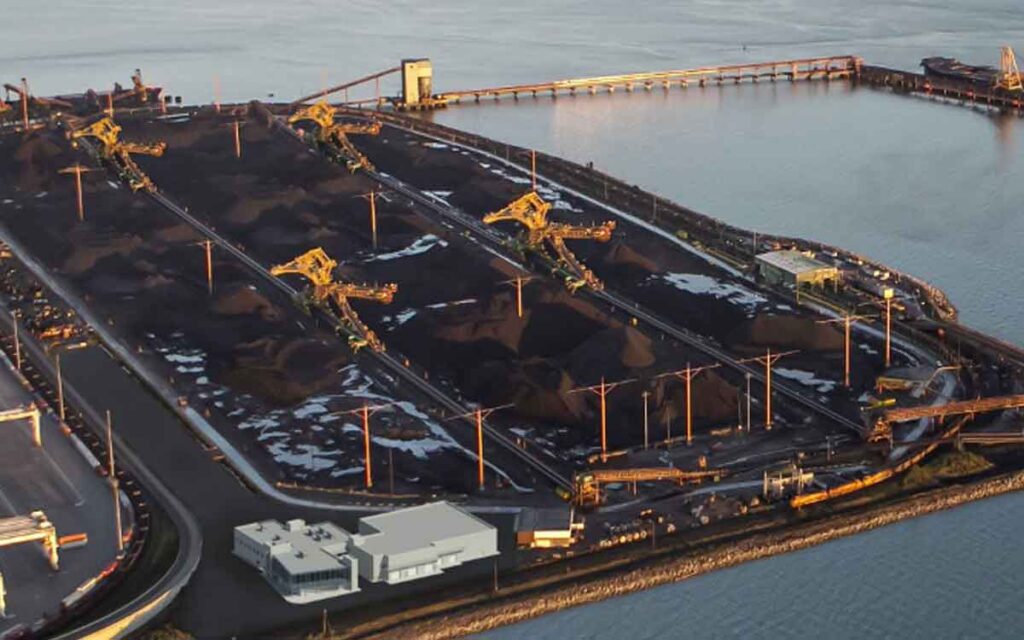

Australia’s exports of coking coal have been trending lower in recent years, largely as a result of supply disruptions caused by bad weather in the main producing state of Queensland. However, they have rebounded in February, with Kpler data showing shipments of 17.86 million tons, the second-highest on record behind the 18.65 million from June 2019. The strength wasn’t really a China or India story, with Japan leading import growth in February, with Kpler assessing arrivals at a three-month high of 4.56 million tons, of which Australia provided 3.86 million.

South Korea also saw higher imports in February, with arrivals of 3.45 million tons, the most since November 2021, according to Kpler. The overall picture that emerges for seaborne coking coal is one where demand in Asia is recovering, with Kpler data showing imports by the region rose for a third straight month in February, likely reaching 19.8 million tons, up from 19.46 million in January and the best month since October. The longer-term outlook is more nuanced, given efforts to reduce carbon emissions in the steel sector.

BHP Group (BHP.AX) the world’s largest shipper of metallurgical coal, believes the market has decades of life left in it as the alternatives to using coal to make steel are either not competitive on a cost basis or unlikely to emerge at scale for decades. However, the company also warned in its results presentation this week that investment in new mines is less attractive, especially in Queensland where the state government imposed sharply higher royalties in July 2022.

While it is to be expected that a company will rail against higher taxes, the trick for BHP is to invest to keep production high enough to meet demand, but low enough to also keep prices strong, but not so low that the Queensland government follows through on its threat to strip the company of its mining licences should it not invest sufficiently.

By Clyde Russell

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters.